Wednesday, December 5, 2012

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

Jim Hall: The Quiet Guitarist

© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Jim Hall is the perfect musical partner.”

- Joachim Berendt, Jazz writer and producer

Today is Jazz guitarist Jim Hall’s eighty-second birthday and the editorial staff at JazzProfiles thought it might be nice to honor him on these pages with a profile that touches upon his many contributions to the music.

Jim Hall is such a quiet, understated and unassuming person that it’s very easy to overlook his many accomplishments in a career that has spanned almost 60 years!

“Jim Hall sometimes is compared by critics to Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt, but then probably every guitarist in jazz has a debt to Christian who, in his short life — he died in 1942 aged twenty-four — became the most important early explorer of amplified guitar as a solo instrument. However, Jim and his trombonist friend Bob Brookmeyer both cite the unsung Jimmy Raney among their influences. From Raney, they say, they developed their integrated and highly compositional approach to the improvised solo, the pensive development of motifs.

Jim started playing guitar professionally in Cleveland Los Angeles New York

Jim had close associations, too, with Paul Desmond, with whom he recorded a series of superb albums for RCA, and with Bill Evans. He and Bill recorded two stunning duo albums together, achieving a rapport that at times was uncanny. Another close associate has been the bassist Ron Carter, with whom he has worked as a duo from time to time since 1984.”

Elaborating further on the duo albums that Jim made with pianist Bill Evans, author Peter Pettinger remarks in his Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings biography:

“One of the mysteries of music that defies analysis is the ability of two musicians to play especially well together, to feel and instinctively adapt to what the other is doing. The duet recording made by Evans and Hall, Undercurrent [and a latter collaboration entitled Intermodulation], exemplified this secret. In this sublime meeting, the artists shared a common ground of musical values, Hall confessing to having long been influenced by Evans. Both, too, had a rtrong feeling for chamber music: the interactive trio was the pianist's aspiration, and Jim Hall's small-group pedigree was high, especially within the intimate settings of the Jimmy Giuffre 3. Quality of sound encompasses a blending of timbres, in this case lovingly conjured; singing tone shines out from every note.

There is a hazard attached to combining piano and guitar, both essentially chordal instruments. Although jazz musicians use alternative chords with ease, the simultaneous choice of two valid but different chords may well not work. Evans and Hall had the intelligence and mutual awareness to escape this snare. And to avoid textural overcrowding, both were conscious of the value of space, every note being made to count in their joint tapestry.”

James Isaacs describes Hall’s value this way in his insert notes to Intermodulation:

“While Evans was bringing jazz piano to a new pinnacle of sheer beauty, Hall was spending the first half of the 1960's as. in the words of the German critic Joachim E. Berendt, ‘the perfect partner.’ He shared the front line with tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins and flugelhornist Art Farmer in two of the outstanding small groups of any decade, and recorded a series of debonair LPs with the late altoist Paul Desmond.”

Since the mid-1980s, thanks to long association with two labels, Concord and Telarc, Jim Hall has performed and made recordings with some of the best and brightest musicians on the current Jazz scene including trumpeters Tom Harrell and Ryan Kisor, trombonists Conrad Herwig and Jim Pugh, saxophonists Joe Lovano and Chris Potter, guitarist Pat Metheny, and bassists Don Thompson, Rufus Reed, Steve La Spina, Scott Colley and George Mraz.

In one of his timeless and superbly written essays for The New Yorker magazine that have been collected in his American Musicians: 56 Portraits in Jazz, Whitney Balliett offered the following depiction of Jim Hall:

“Hall, though, doesn't look capable of creating a stir of any sort. He is slim and of medium height, and a lot of his hair is gone. The features of his long, pale face are chastely proportioned, and are accented by a recently cultivated R.A.F. mustache. He wears old-style gold-rimmed spectacles, and he has three principal expressions: a wide smile, a child's frown, and a calm, pleased playing mask—eyes closed, chin slightly lifted, and mouth ajar. He could easily be the affable son of the stony-faced farmer in "American Gothic." His hands and feet are small, and he doesn't have any hips, so his clothes, which are generally casual, tend to hang on him as if they were still in the closet. When he plays, he sits on a stool, his back an arc, his feet propped on a high rung, and his knees akimbo. He holds his guitar at port arms.

For many years, Hall's playing matched his private, nebulous appearance. When he came up, in the mid-fifties, with Chico Hamilton's vaguely avant-garde quintet (it had a cello and no piano), and then appeared on a famous pickup recording, "Two Degrees East, Three Degrees West," that was led by John Lewis and involved Bill Perkins, Percy Heath, and Hamilton, he sounded stiff and academic. His solos were pleasantly designed, but they didn't always swing. But as he moved through groups led by Jimmy Giuffre, Ben Webster, Sonny Rollins, and Art Farmer, his deliberateness softened and the right notes began landing in the right places.

Then he married Jane [in 1965; she is a psychotherapist], and his playing developed an inventiveness and lyricism that make him preeminent among contemporary jazz guitarists and put him within touching distance of the two grand masters—Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt. Listening to Hall now is like turning onionskin pages: one lapse of your attention and his solo is rent. Each phrase evolves from its predecessor, his rhythms are balanced, and his harmonic and melodic ideas are full of parentheses and asides. His tone is equally demanding. He plays both electric and acoustic guitars. On the former, he sounds like an acoustic guitarist, for he has an angelic touch and he keeps his amplifier down; on the latter, a new instrument specially designed and built for him, he has an even more gossamer sound.

Hall is exceptional in another way. In the thirties and forties, Christian and Reinhardt put forward certain ideals for their instrument—spareness, the use of silence, and the legato approach to swinging—and for a while every jazz guitarist studied them. Then the careering melodic flow of Charlie Parker took hold, and jazz guitarists became arpeggio-ridden. But Hall, sidestepping this aspect of Parker, has gone directly to Christian and Reinhardt, and, plumping out their skills with the harmonic advances that have since been made, has perfected an attack that is fleet but tight, passionate but oblique. And he is singular for still another reason. Guitarists are inclined to be an ingrown society, but Hall listens constantly to other instrumentalists, especially tenor saxophonists (Ben Webster, Cole-man Hawkins, Lester Young, Sonny Rollins) and pianists (Count Basie, John Lewis, Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett), and he attempts to adapt to the guitar their phrasing and tonal qualities.

In his solos he asserts nothing but says a good deal. He loves Duke Ellington's slow ballads, and he will start one with an ad-lib chorus in which he glides softly over the melody, working just behind the beat, dropping certain notes and adding others, but steadfastly celebrating its melodic beauties. He clicks into tempo at the beginning of the second chorus, and, after pausing for several beats, plays a gentle, ascending six-note figure that ends with a curious, ringing off-note. He pauses again, and, taking the close of the same phrase, he elaborates on it in an ascending-descending double-time run, and then skids into several behind-the-beat chords, which give way to a single-note line that moves up and down and concludes on another off-note. He raises his volume at the beginning of the bridge and floats through it with softly ringing chords; then, slipping into the final eight bars, he fashions a precise, almost declamatory run, pauses a second at its top, and works his way down with two glancing arpeggios. He next sinks to a whisper, and finishes with a bold statement of the melody that dissolves into a flatted chord, upon which the next soloist gratefully builds his opening statement.”

Fortunately for all of his many fans, on March 30, 2009 , the Library of Congress sponsored the following video interview of Jim Hall recounting the highlights of his career and his approach to Jazz guitar. Larry Applebaum moderates the discussion.

Saturday, December 1, 2012

Big Band Bonanza – The Way We Were

© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

It would be unfair to say that Jazz today is bereft of big bands.

They abound, it seems, on every college campus that offers a Jazz education program and in a number of European venues, as well [including – as shared here in a previous JazzProfiles feature – the island of Sardinia

But there was a time when big bands were the source for most popular music in the United States Great Britain Europe .

The predominance of this big band era is described in the following excerpt from the venerable Jazz author Gene Lees ’ chapter on the formation of “… the first true Woody Herman band” in his Leader of the Band: The Life of Woody Herman [Oxford

© -Gene Lees /Oxford University Press, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“The Swing Era cannot be dated precisely, since its roots go back to the Paul Whiteman band in the 1920s. It is generally considered to have lasted from the time of Benny Goodman's first big success in 1935 through to the late 1940s, a little more than ten years. Before Goodman, however, there were the Casa Loma orchestra, McKinney

Eventually there were scores of these bands making records, playing on radio, and touring North America, among them those of Georgie Auld, Charlie Barnet, Count Basie, Will Bradley, Les Brown, Benny Carter, Bob Chester, Larry Clinton, Bob Crosby, Sam Donahue, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Jan Garber, Glen Gray, Erskine Hawkins, Earl Hines, Hal Kemp, Stan Kenton, Ray McKinley, Lucky Millinder, Teddy Powell, Boyd Raeburn, Alvino Rey, Jan Savitt, Artie Shaw, Bobby Sherwood, Claude Thornhill,

Jerry Wald, and Chick Webb, all of which were of what we might call the jazz persuasion and featured excellent soloists. Then there were what the hip (in those days hep) fans called the "sweet" bands, despised by the jazz fans as "corny," a term reputedly coined by Bix Beiderbecke to suggest the backward and bucolic. These included Blue Barron, Gray Gordon, Eddy Duchin, Shep Fields, Freddy Martin, Vaughn Monroe, Dick Stabile, Tommy Tucker, Horace Heidt, Richard Himber, Art Kassel, Wayne King, Johnny Long, and Lawrence Welk.

Guy Lombardo repeatedly won the Down Beat readers' poll in the King of Corn category. This was a little unfair. What the Lombardo orchestra was until its leader's death was a museum piece, an unaltered 1920s tuba-bass dance band, quite good at what it did and admired by such unlikely persons as Louis Armstrong and Gerry Mulligan. Usually included in the corn category were the orchestras of Kay Kyser, Sammy Kaye, and Ozzie Nelson, though all three were capable of playing creditable big-band jazz, and the Nelson orchestra was a very good band, again one that Mulligan admires. Trombonist Russ Morgan led what was considered one of the corny bands, and few fans realized he had been a pioneering jazz arranger.

The "big-band era," probably a better term than "swing era," since a lot of successful bands not only didn't swing but didn't even aspire to, reached its peak during World War II, despite the problems bandleaders had in finding personnel when so many young musicians were in military service. As we have noted, the fortunes of the bandleaders and their sidemen and singers were followed avidly in Down Beat and Metronome, but even the lay press got into it when the sequential polygamy of Artie Shaw and Charlie Barnet made news, along with the marriages of Harry James to actress Betty Grable and of Woody's old friend Phil Harris to Alice Faye. These bandleaders were not only treated as movie stars, but sometimes were movie stars—Tommy Dorsey, Artie Shaw, Glenn Miller, Harry James, and Woody among them—appearing in feature films. Almost all of them were at least in short subjects. In some cases, the movies were about the band business, including Second Chorus, in which Shaw uncomfortably portrayed a bandleader named Artie Shaw, and Orchestra Wives, in which the Miller band was prominently featured.

The jazz bands were substantially supported by dedicated young dancers referred to condescendingly if not contemptuously as jitterbugs. Shaw, whose aspirations to high culture were never disguised, particularly despised them, and said so publicly. Newsreels of the period—the movie theaters each week featured short news films, precursors of television news broadcasts—from time to time would show the gyrations of the participants in dance contests. There was a patronizing tone about these observations, particularly when they showed black dancers in Harlem , as if the camera and commentator were examining the rites of a primitive tribe. The inference was inescapable. But the best of these dancers were remarkable, and their athleticism—the men spinning the women at arm's length, throwing them into the air and catching them or slinging them under their legs and over their shoulders, the gyrations wild but controlled—was imaginative and skilled. Combining elements of gymnastics and ballet, this kind of dance was also risky, and we can only imagine how many sprained shoulders and broken ankles were suffered when dancers botched some of their most hazardous maneuvers. Today only a handful of trained professional dancers can do what seemingly half the adolescent populace of North America did as a matter of course in the 1940s. …

Nostalgic fans will tell you that the jazz connoisseurs crowded close to the bandstand to listen with enraptured concentration to the bands and their soloists, while the superficial admirers danced in the back of the ballroom, but the division was not that strict. Some fans alternated the two activities. Nor was the line clear between the "sweet" and the "swing" bands. All bands played for dancers, including those of Duke Ellington and Count Basie, and Basie, who probably never gave a thought to whether jazz was an art form, was considered something of a genius for his anticipation of what dancers desired. Even some of the "sweet" bands allowed space for improvised solos. The Les Brown band, generally considered a dance band, featured intelligent and subtle arrangements by writers such as Ben Homer and Frank Comstock and some first-rate jazz soloists.

And so they traveled, platoons of musical gypsies, unpacking their instruments and music stands and setting up camp in hotel ballrooms in the cities or in the open-air pavilions of small towns and lakeside and riverside amusement parks, even in armories, churches, and skating rinks, bringing evenings of glamour, romanticism, and excitement to audiences, and then packing up and piling into cars or buses at evening's end to travel the two-lane highways of America for yet another in a string of jobs. It must have been a lonely life, but I have never met a musician who regretted having lived it. These men were musical pioneers, as were a few women, like trumpeter Billie Roger s and the vibraharpist Marjorie Hyams, both of whom played in the Herman band.

Once upon a time it was doubted that track athletes would ever run a four-minute mile. Now it is so routine that one has to be able to do it even to qualify for some events. Thus it was with brass and saxophone playing in those dance bands. Trumpet and trombone players, particularly lead players, were called on to play sustained difficult material and to keep it up for hours on end. No symphony woodwind players have ever been required to show the kind of endurance a jazz or dance band demands of saxophone players. This was exploratory music, and Tommy Dorsey, for one, altered the tessitura of trombone forever; now even some symphony players have that kind of technique. Louis Armstrong irreversibly altered trumpet playing, but many symphony players even now cannot do what Harry James, Dizzy Gillespie, and Maynard Ferguson established as norms for that instrument. Symphony trumpet players are not called on to produce the sustained evening-long power of the great lead trumpet players such as the late Conrad Gozzo, or to play the high notes routinely called for by jazz arrangers, notes once considered off the top of the instrument. Harry James with Goodman pushed the instrument higher than it had been before.

The form of the orchestra by then had been defined. In later years some writers would add French horns—Claude Thornhill was the first to do this—and expect the saxophone players to double flutes or other woodwinds. But the basic form had been set, a classic musical unit, like the string quartet or the symphony orchestra, and Woody had built the Band That Plays the Blues up to that configuration as it entered its last days to create the first true Woody Herman big band.”

Set to the music of Holland’s Jazz Orchestra of the Concertgebouw, Henk Meutgeert conducting, and performing Peter Beets’ composition Is It Wrong To Be Right” with Beets soloing on piano and Simon Rigter soloing on tenor saxophone, here’s a retrospective of album cover art from a time when big bands ruled right up to the large aggregations of the present day.

Friday, November 30, 2012

A Tribute to the Music of Gerald Wilson

We always enjoy it when Gerald Wilson "stops by" and brings along some of his music. The tune is Patterns and it features solos by pianist Jack Wilson, Carmell Jones on trumpet, Harold Land on tenor saxophone and Joe Pass on drums with Mel Lewis booting things along from the drum chair. You can locate our previous, two-part feature on Gerald in the blog sidebar.

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Grant Geissman: Studio Jazz Guitarist

© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

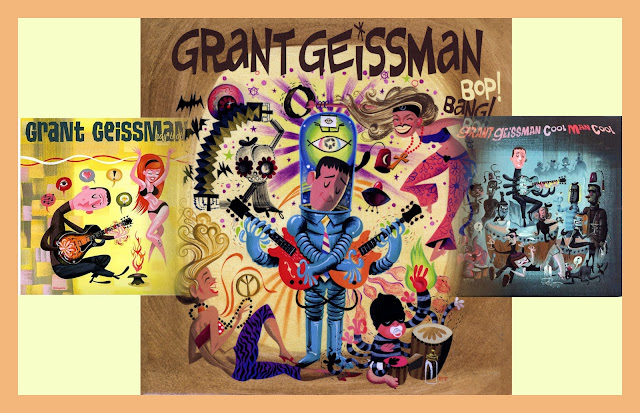

“Grant Geissman's latest CD looks like a five-inch homage to the album-cover artist Jim Flora, with a cartoon of the guitarist serenading a bikini-clad redhead on the cover, and a collage in the center spread crammed with beatnik musicians, cats, birds and a pink elephant. The disc itself is designed like a vinyl record, complete with fake grooves.

Musically, Geissman takes a step into the past too, abandoning his smooth-jazz track record in favor of rootsy sound based in soulful hard bop, with a little New Orleans and upbeat melodies that still go down smoothly without the gloss.

From the Horace Silver-influenced title track to "Theme From Two and a Half Men," which gives the guitarist and Brian Scanlon (on soprano sax) a chance to blow over the sitcom theme, Geissman proves himself to be no wallflower when he puts his mind to it. But often tracks like "Bossa," with wordless vocals by Tierney Sutton, or "Wes Is More," with an excessive section of traded fours and twos with organist Jim Cox, come off more like bossa nova and blues without the necessary roughness.”

- Mike Shanley Review of Grant Geissman’s Say That! CD in JazzTimes APRIL 2006

“Grant Geissman's third in a trilogy of wildly eclectic outings once again has the versatile guitarist indulging in more than a few of his favorite things. From loping funk to boogaloo to earthy blues shuffles, with a haunting ballad, a beautiful samba and an urgently swinging post-bop romp thrown into the mix —along with touches of classical, flamenco and zydeco — he covers all the bases with authority on “Bop! Bang! Boom!

'It's all stuff I'm interested in and like to play, so it just comes out," says the San Jose native who is well known for his improvised guitar solo on Chuck Mangione's 1978 pop crossover hit 'Feels So Good* and more recently for co-writing the theme for the hit CBS-TV sitcom Two and a Half Men ("Men, men, men, men, manly men!*] ‘I have eclectic tastes and the way I play and write follows that. And since this album is on my own label, I get to do what I want!’”

- Bill Milkowski, liner notes

“One of the reasons I created my own label, Futurism, was so that I could explore anything I wanted—which to me is what an artist is supposed to do.”

- Grant Geissman

Like his counterpart, guitarist Lee Ritenour, who is affectionately known as “Captain Fingers” for his legendary ability to play any style of guitar at a moment’s notice, Grant Geissman really knows his way around a recording studio.

Grant is a Pro’s Pro: he brings it; he lays it down; it’s perfect. No need for another take. It’s done. Let’s move on.

Given the amount of money that record producers have to spend to develop an album, Grant’s ability to make it happen and to make it happen right the first time is why he’s first call on most contractor’s lists.

Grant also understands the technical aspects of the studio; he's savvy about the processes involved with making a recording. Whether it’s the sound board, the mix, the use of electronics and synthesizers to create and enhance the music, Grant knows about this stuff.

More importantly, Grant knows enough about all of these elements of engineering sound so that he can make them subservient to the final product – good music.

Grant also surrounds himself with musicians who are at home creating Jazz in a studio environment.

In recent years, Grant has taken matters a step further with the formation of his own label - Futurism Records.

Beginning in 2006 with Say That! and following in 2009 with Cool Man Cool, Grant has offered eclectic Jazz stylings that appeal to a wide range on interests: some Smooth Jazz; some Latin Jazz; some straight-head Bebop – all infused with Grant’s sophisticated studio sensibilities.

Bop! Bang! Boom!, the latest CD in the series, was released by Grant on July 17, 2012

In addition to a whole host of special guest such as saxophonist Tom Scott, guitarist Larry Carlton and keyboard artist Russell Ferrante who join Grant on selected tracks, there is the bonus of the artwork of Miles Thompson that graces these CDs and is very reminiscent of the classic LP cover art that Jim Flora developed for many RCA and Columbia

Here’s what Michael Bloom Media Relations had to say about Bop! Bang! Boom!:

“[This CD] is the third album in a loosely fashioned trilogy that reflects Grant Geissman's shift to more traditional jazz expressions. The powerfully eclectic follow-up to Say That! and Cool Man Cool includes amped-up ventures into numerous genres that reflect Geissman's multitude of passions.

The key to making meaningful music for me is to not limit myself stylistically. I actually can't envision writing an album where every track sounds the same. One of the reasons I created my own label, Futurism, was so that I could explore anything I wanted—which to me is what an artist is supposed to do. I don't know what happens after Bop! Bang! Boom!, it might be completely different. But it's not about having a master plan, it's about writing and recording music that excites and inspires me.”

Geissman co-wrote the Emmy-nominated theme (and also co-writes the underscore) for the hit CBS-TV series Two and Q Half Men. He also co-writes the underscore for the hit series Mike & Molly (also on CBS). As a studio musician, he has recorded with such artists as Quincy Jones, Chuck Mangione (playing the now-classic guitar solo on the 1977 hit "Feels So Good77), Lorraine Feather, Cheryl Bentyne, Van Dyke Parks, Ringo Starr, Gordon Goodwin's Big Phat Band, Joanna Mewsom, Inara George, Burt Bacharach and Elvis Costello.”

Here’s a taste of the music on Bop! Bang! Boom! The tune is Un Poco Español on which Grant plays his mellow-sounding 1972 Hernandis nylon string classical guitar with Russell Ferrante featured on piano.

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Louis Stewart /Mundell Lowe. play Body and Soul. Duets#2

Put your feet up, grab a cup of coffee or tea and relax while listening to some exquisite guitar playing.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Buddy DeFranco and Dave McKenna: Two for the Recording Studio

© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Nobody has seriously challenged DeFranco's status as the greatest post-swing clarinetist, although the instrument's desertion by reed players has tended to disenfranchise its few exponents (and Tony Scott might have a say in the argument too). DeFranco's incredibly smooth phrasing and seemingly effortless command are unfailingly impressive on all his records. But the challenge of translating this virtuosity into a relevant post-bop environment hasn't been easy, and he has relatively few records to account for literally decades of fine work….”

“Dave McKenna hulks over the keyboard…. He is one of the most dominant mainstream players on the scene, with an immense reach and an extraordinary two-handed style which distributes theme statements across the width of the piano.

McKenna is that rare phenomenon, a pianist who actually sounds better on his own. Though he is sensitive and responsive in group playing … he has quite enough to say on his own account not to need anyone else to hold his jacket.”

- Richard Cook and Brian Morton, The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, 6th Ed.

In the 100+ years that Jazz has been in existence, it has been expressed in any number of instrumental combinations: combos, trios, quartets, quintets, sextets, octets, tentets and big bands.

It almost seems that as the popularity, and with it, the fortunes of the music, waned, the smaller the groupings became.

The big bands of the Swing Era were replaced by combos after WW II and these would soon be reduced to piano-bass-drum trios. Sometimes locally-based trios served as pick-up rhythm sections for horn players who traveled the Jazz club circuit of major cities as guest soloists. It was cheaper for them to get booked into local clubs this way. Star alto/tenor saxophonist Sonny Stitt made his living this way for many years.

Throughout its history, Jazz has had a long association with night clubs many of whose owners were looking to pedal booze with the music serving as a convenient backdrop.

Jazz nightspots like The Lighthouse and Shelly’s Manne Hole in southern California, The Blackhawk in San Francisco, the Jazz Showcase in Chicago and Birdland and The Village Vanguard, all of which featured the music as well as sold libations, have become few and far between since their heyday from 1945-65.

Not that these smoke-filled rooms were ever the best environment for the music let alone the musicians, but at least they gave Jazz fans venues in which to hear the music performed on a regular basis.

Duos have always been around the Jazz scene, but they were generally formed by a pianist or a guitarist backed by a bass player, in other words, an instrument to carry the melody while the other played rhythm to keep the swinging sense of metronomic time which is a key feature of Jazz.

This low-key approach was generally favored by some of the smaller rooms that offered Jazz and was usually easy on the wallet of the club’s owner. Adding horns and drums to such an environment would overpower the patrons.

Not surprisingly, with the passing of time and the diminishing of its fans base, Jazz solo piano gigs also became ensconced in some clubs. Occasionally, a guitarist, or a trumpet player with a mute or even a saxophonist who could keep the volume down might drop by to sit-in with these solo pianists.

For many years, one of the best pianists in Jazz was a frequent performer as a solo pianist in clubs in the greater Boston Newport , R.I. Florida

His name was Dave McKenna [1930-2008] and he always maintained that, “[ … because of his fondness for staying close to the melody], I’m not really a bona fide jazz guy”. Instead, he claimed, “I’m just a saloon piano player.” Regulars at the Boston’s Copley Plaza Bar (now the Oak Room), where Dave often performed, rebuffed this modest remark by telling McKenna that he was ‘just a saloon player’ like Billie Holiday was ‘just a saloon singer.’”

Thanks to the late Carl Jefferson’s patronage, many lesser known, but not necessarily less-skillful, solo pianists would have their work showcased on his Concord Records Maybeck Recital Hall [Berkeley , CA

Richard Cook and Brian Morton of The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, 6th Ed. had this to say about the DeFranco-McKenna collaboration:

“Concord Dave McKenna, still as fiercely full-blooded as ever at the keyboard, and musician enough to have DeFranco working at his top level. 'Poor Butterfly', 'The Song Is You' and 'Invitation' are worth the admission price, and there are seven others.”

Here’s what Dr. Herb Wong had to say about the DeFranco-McKenna Jazz alliance in his insert notes to Dave McKenna and Buddy deFranco: You Must Believe in Swing [Concord CCD-4756-2].

© -Dr. Herb Wong, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Though rare up until some 25 years ago, duos now occupy a pivotal niche in jazz. Their interest stretches beyond mere curiosity; two-instrument bands face the challenge of creating musical moments germane to their special environment which neither solo musicians nor conventional small combos can furnish.

Most duos highlight the beauty of musicians of similar styles and schools of thought playing with a preferred consonant sound. On the surface, therefore, the pairing of Dave McKenna and Buddy DeFranco might seem unlikely. "At first thought, Dave and Buddy may not be a perfect fit, since they come from somewhat different directions," recalls Dr. Dave Seiler, Director of the University of New Hampshire Jazz Band

The background trail leading to this unusual pairing is of interest. Born in the vision of one Joe Stellmach, a devout fan and good friend of both McKenna and DeFranco, this recording was inspired by the spectacular match-ups of DeFranco with super piano icons Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson back in the 1950s. The prospect of DeFranco's thorough mastery of the instrument (with his modern harmonic vocabulary and improvisational skills) brought together with the extraordinary pianism of McKenna (one of the most triumphant post-Tatum pianists) was Stellmach's dream.

"I was inspired to bring Dave and Buddy together - specifically Dave as the third prodigious jazz pianist to be coupled with Buddy," said Stellmach, who was the catalyst in gaining the enthusiasm of Concord Jazz to make this recording. Less than a week after the teaming was agreed to, a debut concert was organized by local piano great Tom Gallant and the aformentioned Dr. Seiler for October 9, 1996 at Portsmouth , New Hampshire New York

DeFranco's esteem for McKenna is markedly illustrated by this anecdote: "Two summer ago in New England , a friend of Dave 's asked me if I'd like to go hear him play solo in a hotel by the coast. I had a plane to catch later on, so I decided to catch one set and then fly home. I wound up listening to the entire three sets."

McKenna is an anomaly in the world of jazz pianists; his two-handed style is so rhythmically powerful that he's essentially self-sufficient. Ace trombonist Carl Fontana, who has played with McKenna many times, simply said, "Dave isa band. You don't really need one when he's around!" Pianist Dick Hyman agrees, "He's his own rhythm section. The left hand plays a 4/4 bass line, the right hand plays the melody, and there's that occasional 'strum' in between - like three hands." Check his right hand off-beat single notes, and unpredictable spaces promoting accents that create ear-tugging reactions. Reminiscent of Tatum, McKenna's arpeggios at times seem like they're 50 feet long.

"Dave plays a different way - an orchestral way," DeFranco elaborates. "Of course, Errol Garner and Oscar Peterson had it too, but Dave has a bass line going on all the time. He has the orchestral melodic part, and those exciting chord progressions, but somewhere he sneaks in what might be 'brass figures,' and it's fascinating to wonder how he gets them in. He inserts these figures while everything else is going on."

McKenna explains it quite simply: "I like to play a long line - like a horn player's single notes, which also equate to single notes on a bass. Well, sometimes I'll pause - take a breather in that line, and on occasion just throw in a chord or two." His predilection for single note lines suggests that he has listened a great deal more to horn players than he has to pianists.

Buddy DeFranco is the titan of the modern jazz clarinet who had taken his instrument to the peak of mastery decades ago and has maintained this preeminence internationally since the forties. He has pushed his digital precision to its technical boundaries, and early on merged his blazing, flawless execution with the vital force of Charlie Parker's harmonic approach. With his devastating speed and gorgeous, fluid tone, he improvises with emotional candor and blows nuclear ideas that explode with surprising hues and shapes.

An accomplished clarinetist himself, Seiler says simply "Buddy is a clarinet player's clarinet player." …

Speaking about DeFranco, McKenna said firmly, "It was a real pleasure working with him. Man, he's got it all! In a duo you have to be busy all the time. It's one of the hardest things to do, but with a great horn player like Buddy - that's something else! I really enjoy his musicality."

In a duo, each musician is truly half of what happens. It's a matter of the freedom to express and letting things happen with complete confidence — a process which shows the music is worthy of risk. There's an enchanting aura about the numeral "two". This duo reflects that mystifying magnificence. There is something pristine about combining a piano note and a clarinet note. Dave McKenna and Buddy DeFranco share in tandem a striking set of properties of integrity and musical character only mature creative players experience. Their sophisticated knowledge and simpatico are self-evident.

DeFranco said it well: "If it doesn't swing, it isn't happening!"

You can savor the duo delight that is Dave McKenna and Buddy DeFranco in the following video tribute which features their performance of Tadd Dameron’s If You Could See Me Now. [Click on the “X” to close out of the ads should they appear].

Saturday, November 24, 2012

Paramaribop

© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Music by Anton Goudsmit, Efraim Trujillo, Jeroen Vierdag and Martijn Vink

A few years ago a friend in Holland Groningen

It was my first introduction to a style of Jazz that some refer to a “Paramaribop,” which derives its name from blending “Paramaribo Suriname

By way of background, Suriname South America and was for many years ruled by the Dutch as Dutch Guiana .

Jazz would emerge from the interactions of these cultures in early 20th century New Orleans

Juan Pablo Nahar was born in Paramaribo , Suriname

Eventually moving to Holland New York

Upon his return to The Netherlands, Pablo organized workshops at Bijlmer Park Theater in Amsterdam that resulted in concerts of the fusion music then being experimented with by musicians of Surinamese and Antillean origin who lived in that area of the city.

In 1981, along with drummer Eddie Veldman, Pablo co-founder the now legendary Surinam Music Ensemble which pioneered the development of "Paramaribop,” a unique combination of Afro-Surinam Kaseko/Kawina rhythms and the abstract and more complex harmonies of Bebop.

A number of young, Dutch Jazz musicians worked in Pablo Nahar’s groups and subsequently went on to become great supporters of Paramaribop.

Among them are guitarist Anton Goudsmit, tenor saxophonist Efraim Trujillo, bassist Jeroen Vierdag and drummer, Martijn Vink.

While all of these players have made a huge footprint on the Dutch Jazz scene in other contexts – the New Cool Collective, the Metropole Orchestra and Big Band, the Jazz Orchestra of the Concertgebouw, the Rotterdam Jazz Orchestra, Nueva Manteca, small groups headed by reed players Tinke Postma and Benjamin Herman - they formed a group in 2005 which has since become known as The Ploctones, which plays a style of music that has a deep allegiance to Paramaribop.

Nominally led by guitarist Goudsmit who was awarded the VPRO-Boy Edgar Prize for 2010 as the best Jazz musician in Holland

In his Volksrant review of their first CD Live Op Het Dak [VPRO Eigenwijs–EW 0578],Koen Schouten described the group this way [please forgive the Dutch-English tone as an online translator was used]:

“A group with a rare solidity, determination and flexibility. A genuine four-headed monster.

Whether it concerns a rhythmic tour de force, a fun idea or a tearjerker, the quartet always sounds solid and the group members never cease to surprise each other. The changes and shifting times are whizzing past our ears.

With his ardent and passionate guitar playing the versatile and innovating Anton Goudsmit developed into a musical chameleon without losing his recognizable and characteristic style. His miscellaneous compositions are the base of poetic improvisations and flashy power performances.

A critic of the British ‘Guardian’ described Goudsmit as: ‘the kind of musician that makes you wonder where the fire escape is’.

He graduated cum laude at the Amsterdam Music Conservatory in 1995 and today he can be reckoned as one of the most influential guitarists of the

Jeroen Vierdag is a strong and creative bass player who lifts the band up to a higher level with his driving groove and great virtuosity, competing with his 6-string colleague. He’s been around in the field of pop, jazz, Latin and Brazilian music.

Martijn Vink is an extremely passionate drummer with a peerless technique. One moment he raises the roof and the next he colors and refines with the subtlety of a musical box. He is the regular drummer of the internationally renowned Metropole Orchestra and collaborated with many jazz giants like Pat Metheny, Herbie Hancock and John Scofield.

Tenor saxophonist Efraim Trujillo stands out in hectic compositions as well as in a more ambient repertoire due to his open and dynamic playing. Because of his abundance of experience and ability to do anything with his instrument he renews and upgrades the music he plays and makes a concert of this group a special experience for the audience and the band members, time and again. Trujillo

Since 2010, the quartet has adopted a new name – The Ploctones – and you can learn more about them on their website – www.ploctones.com/

See what you think of Paramaribop as Anton, Efraim, Jeroen and Martijn perform their version of it on a tune entitled Boom-Petitwhich serves as the soundtrack to the following video.

One thing is certain, Paramaribop is sure to move your ears in a different direction.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

OCCC MEET 2012 MEMBERS EDITION

Last event gathered 19 members of OCCC at Taman Selera, Miri and we had a long day of full excitement. This was our first attempt to organize such event and it seems worked as planned. Congrats to all OCCC members!

One of the happening activities, football match among Team A and Team B.

Photoshoot time among drivers and cars, waiting for Mat Rock AE80 and his clan.

"Hey, is that a Toyota 2000GT?"

Carrom match again, this time Marol, Roy, and his mate.

Spa clans, moments before they headed off to the House of Massage.

Edy: Go away! It's my ball(s).

...and the team that lose will have to do the BBQ.

Just right... Leh blocked Jul while Hanif quickly made a shot.

OK back to the chicken wing. Mazli and Hisham worked really hard to finish their task while the others started to enjoy the delicacies.

Photographing a photographer.

Daughter (purple shirt): Papa, you forgot to open the lens cap.

Edy: Syhh.. Don't tell that loudly.

Salleh the KE10 lover.

GF: Honey! Where are you? I have been waiting at home for 3 hours. I thought we have a date today.

Boy: Err... (speechless)

Fishy tricks by Romy (smiling from ear to ear) to defeats Hanif.

Cikgu and his son worked hard to prepare the meals.

At 4 o'clock, we settled down and heading to Luak Esplanade for 'makan angin' and wangan session.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)